Source: Eldad Yechiam, "Acceptable Losses: The Debatable Origins of Loss Aversion" in Psychological Research 83(7):1327-1339 (Oct. 2019)

The Context.

As with many things in finance and investing, there is a strong tendency to over-apply concepts and uncritically paste ideas across contingent contexts.

Perhaps this is an aversion to uncertainty more than anything else.

Perhaps in the post-electric media age (👋 specter of Marshall McLuhan), this aversion has become pathological.

Certainly, I am not perfectly immune to my own critique. But, hopefully I cannot be accused of laziness, intellectual or otherwise. And, as a reminder (to myself), my purpose with these Field Notes is to habituate a self awareness and probing ethic more than it is to cement a conclusion or strobe stats of new subs only to fall victim to the internet versions of Scylla and Charybdis. ☠️

More specifically, I have observed a tendency to invoke the notion of "loss aversion" – as used by the (in)famous works of Kahneman and Tversky – to explain (away) all types of investing behaviors.

My personal and crude heuristic in seriously engaging in topics related to neurofinance, behavioral economics, and the like is as follows:

If someone invokes Kahneman but has never explored Gigerenzer (see, e.g. Field Notes 22 and 106), there's likely a problem.

And maybe, I've developed a moderately unhealthy aversion to this appropriation of loss aversion...

The Details.

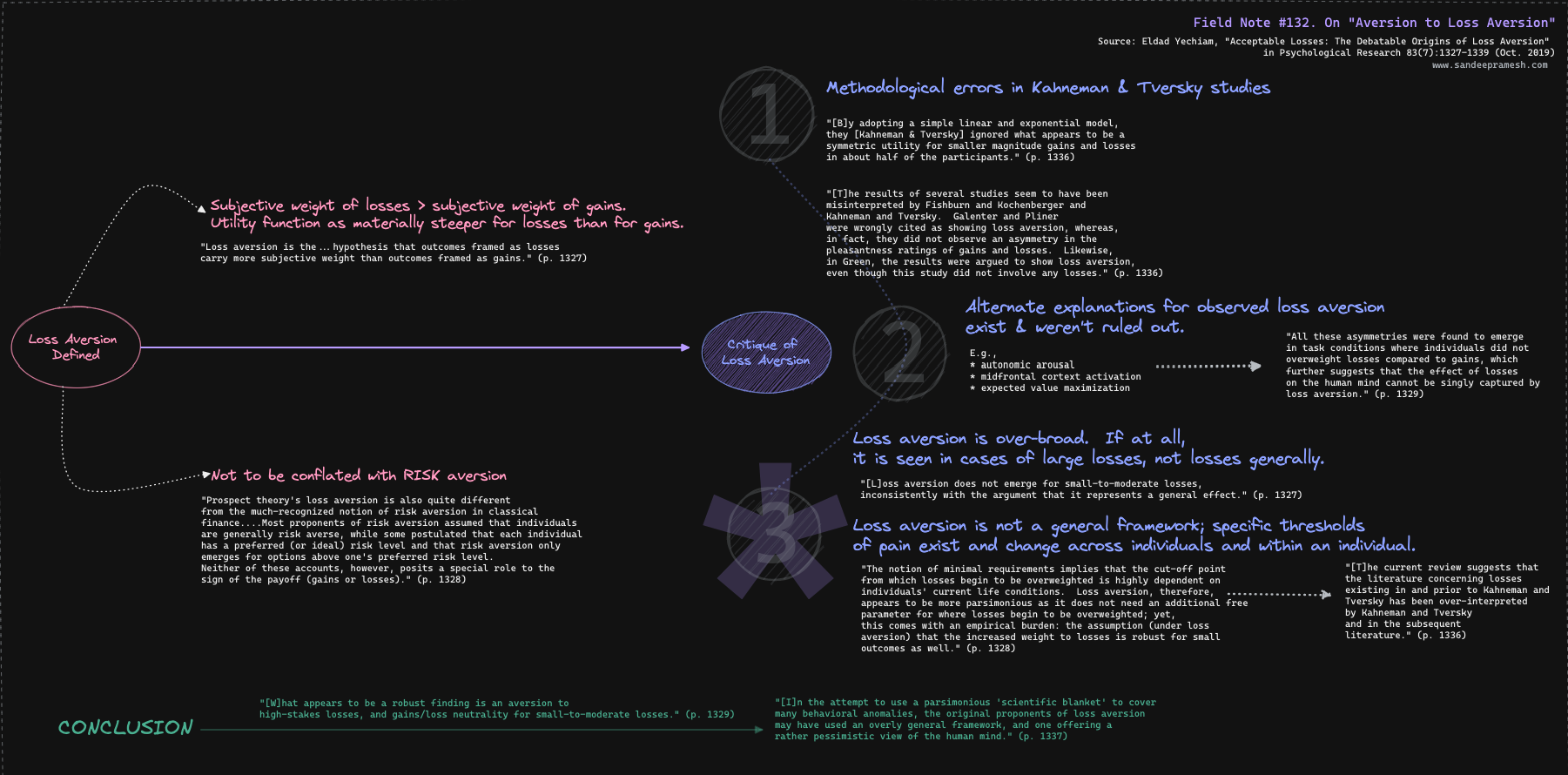

As the source for this Field Note argues, Kahnemanian "loss aversion" suffers from 3 problems:

- Methodological errors in the loss aversion studies

- Failure to account for alternative explanations in the experiments

- Over-application of the concept, purporting a general framework instead of a special case that probably only applies to decisions in the face of large losses, a.k.a., "risk of ruin" (a pet topic of mine; see, e.g., Field Notes 17, 58, 62 and several others indexed + searchable on my improved personal website 👍)

One troubling issue is that loss aversion's existence may be further reduced to even narrower cases of significance as applied to a professional investing context.

Specifically, when incentives aren't properly aligned between GPs/fund managers and LPs--and when LPs are treated as passive money as opposed to Besozian customers-- confrontations with "risk of ruin" are miscategorized as "small losses" potentially removing the special case application of loss aversion pointed to in #3 above.

In the above case, the asymmetry can be framed not so much in the supposed steepness of utility functions for losses vs. gains; rather, the framing that strikes harder is the sinister asymmetry of privatizing gains, while socializing losses.

The Mind Map.